It is getting very personal indeed.

Companies in all industries are actively looking into the possibility of harnessing personal data for making better decisions in many realms:

- How to better invest their capital and use their resources?

- How to customize certain products to satisfy individual customer needs?

- Is a given individual eligible for insurance coverage? If so, at what price?

- Is a given individual eligible for consumer credit? if so, what kind of credit product?

This renewed interest for personal data as a decision enabler coincides (or perhaps it is explained) by the fact that we live in a time where technology allows for tremendous amounts of personal data to be generated, collected and processed at a mind-numbing scale and speed.

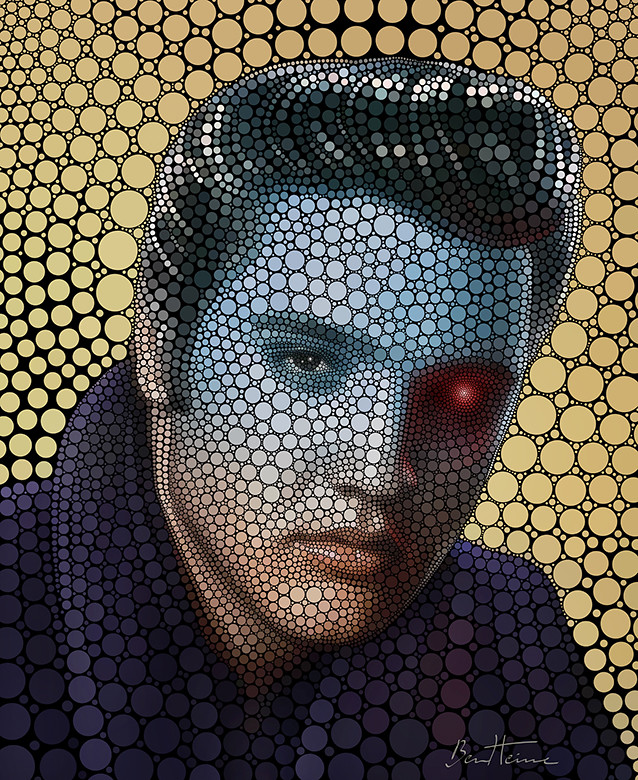

So, if we take a look at this future that we live in, there is no escape to the realization that all of this can go really bad. There seems to be this latent and very possible dystopia waiting to occur that is eloquently portrayed in some of the posters of the CPDP 2017 conference:

It is not such a stretch of the imagination to think of a world where machines located in remote and undisclosed places get to make obscure yet critical decisions that affect our lives in all kinds of ways. A machine that decides that someone will not be covered by insurance, a machine that decides that someone is inapt for a given job, a machine that decides whether you are liable to pay a big fine. All without a clear explanation… all without a reason that seems fair or at least mildly intelligible.

It is important that we all realize that this kind of dystopian future is very possible. Preventing it from happening is perhaps one of the main challenges to be addressed not just in the realm of fintech but in many other spaces. All of us as citizens, legal practitioners, regulators, entrepreneurs and activists have a lot of work to do to prevent it from becoming a reality and Data Protection Law offers a very handy toolkit for doing just that. All kinds of legal operators (judges, regulators, legal practitioners) should keep this latent dystopia in their minds when they go about the very sensitive work of giving meaning to the 200 pages of the GDPR, for example.

But no matter how urgent and critical that challenge is, we should also admit that it is not the only one. At Kreditech, for example, I have seen many ways in which the right use of automated decision making can have a very positive impact on people’s lives.

We have the good fortune to employ people from the consumer credit 1.0 world who are working closely together with the data-scientists who build all these spooky algorithms. Whenever these two get together, the former very readily admit that no credit policy, credit officer or respectable credit analyst would have ever considered issuing loans to some of the people that "our algorithms" issue loans to.

Initially, this sounds very concerning: Why would we ever issue loans to this people?

The fact is, however, that our data-scientists have consistently observed in the data that a big chunk of this very same people that would have been denied access to credit by 1.0 Lenders are actually very good at repaying their loans in time. We could even hypothesize that there must have been some kind of bias in the way creditworthiness was assessed by humans (and in the old methods) that prevented some people (perhaps due to superficial perceptions related to their socioeconomic status) to gain access to consumer credit.

The fact is, however, that our data-scientists have consistently observed in the data that a big chunk of this very same people that would have been denied access to credit by 1.0 Lenders are actually very good at repaying their loans in time. We could even hypothesize that there must have been some kind of bias in the way creditworthiness was assessed by humans (and in the old methods) that prevented some people (perhaps due to superficial perceptions related to their socioeconomic status) to gain access to consumer credit.

This is rather revolutionary: We might have in our hands the kind of technology that has the potential to help us advance a very important agenda: the agenda of inclusion. In the case of Kreditech: The agenda of financial inclusion. But this could be happening in insurance as well in the sort of mysterious and unpredictable way that innovation tends to happen. What if machines are able to see something in the data that opens the possibility of affordable insurance coverage for individuals/SMEs that have been historically deemed to be too risky to be insured?

The realization of these possibilities should bring us to our second challenge: That whenever we are engaged in the laborious task of construing and giving meaning to Data Protection Law, we make sure that we strike the right balance between building regulatory frameworks that impede the dystopia that was prophesized ad-nausea in CPDP 2017 and the need to enable innovation, the kind of innovation that lifts us and keeps us moving forward.

The realization of these possibilities should bring us to our second challenge: That whenever we are engaged in the laborious task of construing and giving meaning to Data Protection Law, we make sure that we strike the right balance between building regulatory frameworks that impede the dystopia that was prophesized ad-nausea in CPDP 2017 and the need to enable innovation, the kind of innovation that lifts us and keeps us moving forward.

It is very important that we go about that discussion with open minds and open hearts: How do we get this balance very right? Innovation is desirable and important and can be harnessed for the good of mankind. Frank Pasquale and Nicholas Diakopolous, for example, seem to propose an interesting first approach to this in the form of Algorithmic Governance and accountability. That might just be the way to move forward: Understanding that algorithms are not necessarily evil but need proper governance and accountability models. That seems like a very interesting discussion.

But there is also a very unproductive and terrible way to go about this issue: The way of demonizing businesses and insisting that DPAs build a corpus of Law that stifles and regulates innovation away. A world-view that sees regulation as conduit of our worst fears and our worst fears only, leaving no room for the best of our aspirations.

CPDP 2017 was a great event but it was very disappointing indeed to hear very senior and influential policy-makers demonizing certain business models without any sophisticated or nuanced arguments, on the basis of, for example, inacurate media coverage about the number of data-points used for decision-making. It was also very sad to see that none of the tech giants that attended the conference insisted on the need to preserve innovation and harness it for the good but seemed busier with looking cool and concerned and in the eyes of the Privacy Community.

One can only wish that whenever we all go hunting for latent dystopias, we don’t end-up shooting at some of the practices and technologies that could bring us closer to certain outcomes which, analyzed more carefully, look more like the stuff of utopia.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed by the author in this post are strictly personal and do not reflect the official position of the Kreditech Group.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed by the author in this post are strictly personal and do not reflect the official position of the Kreditech Group.

Tweet

No hay comentarios.:

Publicar un comentario

Se reciben comentarios: