The mere notion of Rio is exciting. Football and Samba, Copacabana and Ipanema, Garotas and Bossa Nova. Most recently, the world-cup broadcasts portrayed the city in full HD as a sort of idilic landscape surrounded by hills that seem to protrude directly from the sea.

It is true: The landscape is breathtaking. When you get there, if you happen to talk to a local, a Paulista living in Rio perhaps (Paulista being the demonym used for referring to people born in Sao Paulo) you will most certainly hear a variation of: "Rio is a very ugly city that happens to be located in an amazingly beautiful place". And that seems to be exactly the case.

Apart from the subtle elegance of certain residential areas for the affluent, Rio de Janeiro is not precisely an urban beauty. Copacabana, for example, is far away from being the upscale beach destination that people living in cold places tends to fantasize about. From the distance, one thinks of Copacabana as the Brazilian version of Cancún: A lavish, almost obsessively opulent concoction of beachy amusements.

But getting there under that assumption is disappointing. Much before reaching the legendary beach-front Avenida Atlántica by any means of transportation, a visitor must take at least a glimpse of the other face of Copacabana: a neighborhood that is almost entirely composed of moderately high-rise buildings conceived with zero regard for aesthetics. The architecture, with very counted exceptions, is hideous, and the feeling is that of being overwhelmed by a never-ending sequence of cheap souvenir-shops, greasy restaurants and unhygienic fruit stores.

And then one gets to Avenida Atlántica, the place where everything happens. La Avenida Atlántica is a 4km seaside avenue that borders the whole of Copacabana and Leme and seems to be built with the sole purpose of embodying even the wildest Rio-de-Janeiro fantasies ever conceived.

There is definitely something about Avenida Atlántica, but then it is also not the architecture. The further away one gets from the beach-front, the uglier the constructions get, but even there by the beach the buildings remain ghastly. Not as horrible as the buildings a few blocks away, but still bad enough to make them look as if someone had put them there in a conscious effort to blemish the natural beauty of the landscape.

Perhaps the charm of it lies in the fact that Avenida Atlántica seems to divide two worlds: A busy Rio de Janeiro that works and commutes and a Rio de Janeiro that is all about sun and fun. It does not matter if it is a Tuesday or a Sunday, Copacabana seems to be always inhabited by a certain race of beach people with marked muscles and tanned skin. And these beach-dwellers, together with the other Cariocas, the busy ones, create on the onlooker the irresistible and perhaps unique impression of being witness of the harmonious coexistence of two opposites: a beach paradise and a mega-city. An urban beach of sorts.

La Avenida is at the very core of this blend. It is the gateway from one world to the other and when the sun is shining it is everything that one have day-dreamed about when thinking about Rio de Janeiro. There is music on the streets, there is caipirinhas, there is this beautiful landscape, there is all that beautiful people. Walking all the way to the Fort of Copacabana while getting lost in this boundless beach titillation is something that everyone should do at least once in a lifetime. Stopping by for a cold coconut in one of those beach-bars and drinking its water slowly and having the luck of stumbling upon the right street musicians and simply getting carried away by all of this awesomeness are just reasons good enough to go to Rio. It is perhaps why we go to Rio in the first place. At least in the subconscious parts of our minds we all long for this.

Past the fort of Copabana, just at the end of Avenida Atlántica, the beach thrill is not over. You are fortunate enough to go straight from one of the most legendary beaches in the planet to another: Ipanema. The beach that gave birth to that song and that story about a girl who walks just like a Samba and sways so gentle that when she passes each one she passes goes Aah."

Ipanema offers the same kind of beach exhilaration and a very posh climax: Leblon. Anyone looking for a good glimpse at the comforts of the affluent in Latinamerica can start looking here. Posh apartment buildings, big spaces, up-scale shopping and, at last, a place in Rio with harmonious, well-thought residential architecture. Unlike Copacabana, strolling around Leblon and Ipanema is a pleasant experience. It is great to walk around and find grateful culinary surprises in the whereabouts of Epitácio Pessoa avenue and simply enjoying the parsimony of the neighborhoods of the rich, seemingly more relaxed than the rest of Rio and very archetypical of the urban residential areas of the latinamerican elites: Impudent, obsessed with security, luxurious, sober, elegant.

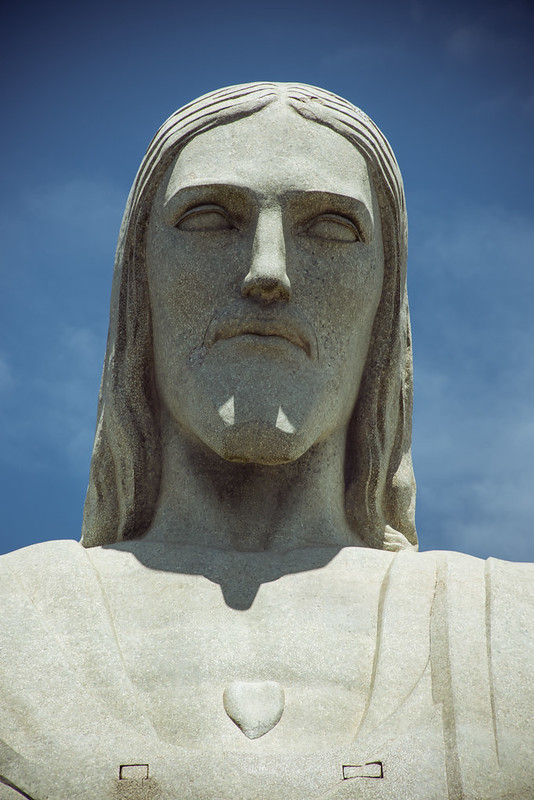

And then there are the carioca touristic destinations per excellence: Christ the Reedemer at the top of the Tijuca national park and the fabled Sugarloaf Mountain. The former is almost the confirmation that Rio de Janeiro is a city that wants to have it all: The physiognomy of a busy megalopolis, a paradisiac beach landscape and its very own natural reserve in the middle. Seen from up-close, O Cristo Redentor is rather dissapointing: A bit smaller than what we saw in television, a bit pale, a bit crowded, a bit inaccessible, a bit too far-away. It is a good idea to book a shuttle online at the national park's website to avoid some of the transportation hassle.

The views from up-there, however, are not disappointing. There is almost a 360 degrees view of the city to enjoy and roughly everything can bee seen: From downtown to the Rodrigo de Freitas lake, in the middle of the city, from the heart of Leblon to Botafogo, with the Sugarloaf mountain in the background. And anyone looking for views has to go exactly there, to the mythical little mountain that seems to be put in place just in the corner spot: Somewhere exactly between Botafogo and Copacabana. Yes: this is one more of those clichés for tourists, but it is worth it. The best views of urban Rio and its intricate relation with the atlantic ocean are to be found up there, on top of o pão de açucar. From the right spots, without moving an inch, an onlooker is able to get a breathtaking view of the mountainous skyline, all the way from the amazingly green Praia Vermelha to Ipanema, with the most beautiful view of Copacabana in the middle.

It is from up there that Rio presents itself as this never-ending latinamerican beach fantasy that everyone dreams of. The mountains, born in the sea to scratch the clouds, are perhaps an extra surprise, an unexpected reason for awe. No visitor should miss these sights.

And then one gets to Avenida Atlántica, the place where everything happens. La Avenida Atlántica is a 4km seaside avenue that borders the whole of Copacabana and Leme and seems to be built with the sole purpose of embodying even the wildest Rio-de-Janeiro fantasies ever conceived.

There is definitely something about Avenida Atlántica, but then it is also not the architecture. The further away one gets from the beach-front, the uglier the constructions get, but even there by the beach the buildings remain ghastly. Not as horrible as the buildings a few blocks away, but still bad enough to make them look as if someone had put them there in a conscious effort to blemish the natural beauty of the landscape.

Perhaps the charm of it lies in the fact that Avenida Atlántica seems to divide two worlds: A busy Rio de Janeiro that works and commutes and a Rio de Janeiro that is all about sun and fun. It does not matter if it is a Tuesday or a Sunday, Copacabana seems to be always inhabited by a certain race of beach people with marked muscles and tanned skin. And these beach-dwellers, together with the other Cariocas, the busy ones, create on the onlooker the irresistible and perhaps unique impression of being witness of the harmonious coexistence of two opposites: a beach paradise and a mega-city. An urban beach of sorts.

La Avenida is at the very core of this blend. It is the gateway from one world to the other and when the sun is shining it is everything that one have day-dreamed about when thinking about Rio de Janeiro. There is music on the streets, there is caipirinhas, there is this beautiful landscape, there is all that beautiful people. Walking all the way to the Fort of Copacabana while getting lost in this boundless beach titillation is something that everyone should do at least once in a lifetime. Stopping by for a cold coconut in one of those beach-bars and drinking its water slowly and having the luck of stumbling upon the right street musicians and simply getting carried away by all of this awesomeness are just reasons good enough to go to Rio. It is perhaps why we go to Rio in the first place. At least in the subconscious parts of our minds we all long for this.

Past the fort of Copabana, just at the end of Avenida Atlántica, the beach thrill is not over. You are fortunate enough to go straight from one of the most legendary beaches in the planet to another: Ipanema. The beach that gave birth to that song and that story about a girl who walks just like a Samba and sways so gentle that when she passes each one she passes goes Aah."

Ipanema offers the same kind of beach exhilaration and a very posh climax: Leblon. Anyone looking for a good glimpse at the comforts of the affluent in Latinamerica can start looking here. Posh apartment buildings, big spaces, up-scale shopping and, at last, a place in Rio with harmonious, well-thought residential architecture. Unlike Copacabana, strolling around Leblon and Ipanema is a pleasant experience. It is great to walk around and find grateful culinary surprises in the whereabouts of Epitácio Pessoa avenue and simply enjoying the parsimony of the neighborhoods of the rich, seemingly more relaxed than the rest of Rio and very archetypical of the urban residential areas of the latinamerican elites: Impudent, obsessed with security, luxurious, sober, elegant.

And then there are the carioca touristic destinations per excellence: Christ the Reedemer at the top of the Tijuca national park and the fabled Sugarloaf Mountain. The former is almost the confirmation that Rio de Janeiro is a city that wants to have it all: The physiognomy of a busy megalopolis, a paradisiac beach landscape and its very own natural reserve in the middle. Seen from up-close, O Cristo Redentor is rather dissapointing: A bit smaller than what we saw in television, a bit pale, a bit crowded, a bit inaccessible, a bit too far-away. It is a good idea to book a shuttle online at the national park's website to avoid some of the transportation hassle.

The views from up-there, however, are not disappointing. There is almost a 360 degrees view of the city to enjoy and roughly everything can bee seen: From downtown to the Rodrigo de Freitas lake, in the middle of the city, from the heart of Leblon to Botafogo, with the Sugarloaf mountain in the background. And anyone looking for views has to go exactly there, to the mythical little mountain that seems to be put in place just in the corner spot: Somewhere exactly between Botafogo and Copacabana. Yes: this is one more of those clichés for tourists, but it is worth it. The best views of urban Rio and its intricate relation with the atlantic ocean are to be found up there, on top of o pão de açucar. From the right spots, without moving an inch, an onlooker is able to get a breathtaking view of the mountainous skyline, all the way from the amazingly green Praia Vermelha to Ipanema, with the most beautiful view of Copacabana in the middle.

It is from up there that Rio presents itself as this never-ending latinamerican beach fantasy that everyone dreams of. The mountains, born in the sea to scratch the clouds, are perhaps an extra surprise, an unexpected reason for awe. No visitor should miss these sights.

But there are at least two other Rios. All the way downtown, Rio de Janeiro is the embodiment of the decadence of latin-american urban centers. The traffic is unbearable, waste disposal is flawed to the extent that there are improvised garbage disposal points all over the city and last but not least: Poverty shows its face everywhere. A couple kilometers away from the beach titillation, Rio de Janeiro is hideous: Its historic landmarks are neglected, the modern architecture of the office buildings is grim and gray and there is this constant feeling of unsafety punctuated by a nauseating smell of pee and garbage. One hundred years of failed democracies have turned the hearts of latin-american cities into playgrounds for drug-dealers and crooks and Rio de Janeiro is not the exception. Apart from the legendary nightlife in Lapa, there is no business near downtown Rio for any visitor after 5pm.

Not content with that, Rio brings another set of opposites very closely together and epitomizes latin-american cities in one more way: It denounces, perhaps like no other city in the continent, the fact that latin-americans have developed too much of a thick skin towards rampant, grotesque inequality. In Rio, people bordering the line of misery coexist seemingly peacefully, at a shockingly cross-the-street distance, with the kind of people who live in two-story houses with swimming pools. This entanglement is so palpable, so blatantly obvious, that an outsider is left with no choice but to ask herself: How is this possible? How can misery and luxury look at each other so closely in the face without blinking?

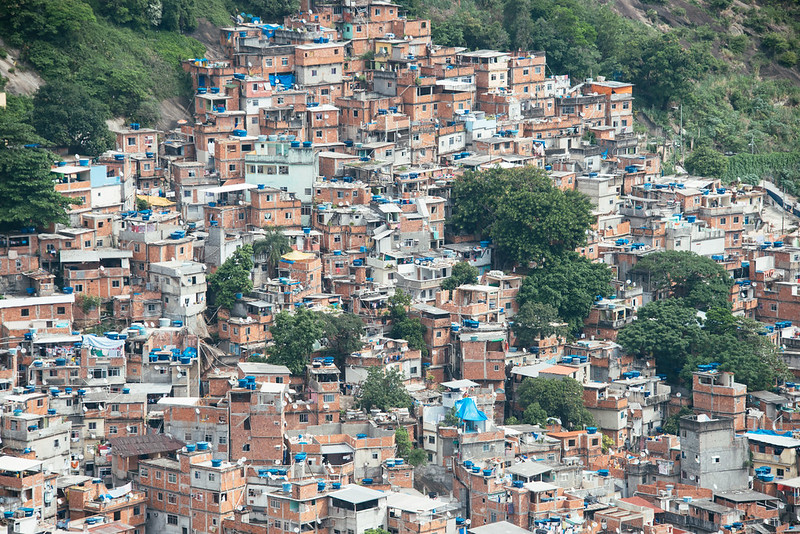

This indolence is most apparent in the world-renowned Favelas, which are the Brazilian version of slums, made famous by movies such as City of God. These slums are the result of mass migration from the countryside to the cities, which is probably the one phenomenon responsible for most of the misery belts in latin-america. They have become notorious for gangsterism and drug-related violence, to the point that some of them are literally run by local drug-lords who bribe or kill the way out of the reach of the law. As a matter of fact, The favela drug-lords become de-facto law-givers, as Boaventura de Souza has suggested in his research, perhaps one of the most exciting works of latin-american legal sociology.

The biggest of all Favelas is La Rocinha, seemingly as full of miseries as it is full of ironies. It houses some of the poorest people in Rio de Janeiro but it also happens to offer some of the most beautiful views of the city. It is not an exaggeration to say that anywhere else in the world, views like these would be the privilege of the elites, but not in Rio. In this city the favela inhabitants are the undisputed kings and queens of the hills.

And there are so many. Only La Rocinha is home to about seventy thousand people. In fact, seen from the right perspective Rio de Janeiro is not really a city surrounded by some Favelas but actually a group of Favelas who happen to be decorated by a city. Any visit to Rio would be incomplete without taking at least a glance at this reality, so it is not a surprise that there is a growing menu of favela-related tourism that seems to exploit this misery by packaging it and selling it to the kind of westerners who are willing to consume it as entertainment.

A dignified way of being a witness to this facet of Rio (and this is said with the bias of someone who opted for it) is perhaps Marcelo Armstrong's Favela Tour. It picks up visitors in a van directly from their hotels and takes them to Vila Canoas and La Rocinha, two very different favelas not so far away from each other. The first one, Vila Canoas, is a so-called pacified Favela, which is an euphemism for referring to the favelas who have been the field of operations of the UPP (Pacifying Police Units), elite police squads formed with the aim of fighting the drug-lords and dismantling their networks of influence.

It is not clear to me whether Vila Canoas has been subject to this strong-hand treatment but the fact is that it is free of drug-violence and very tourist-friendly. Visiting groups can roam almost freely, take pictures and get a closer look at the favela way of life. Its closeness to Sao Conrado, one of the most affluent neighborhoods in Rio de Janeiro, makes it the perfect place for exploring the inequality issue. A luxurious condominium, just across the street, says hi and begs exactly for that question: How is it that latin-america became so complaisant with this ruthless one-sidedness, with this dreadful iniquity?

That is probably a very hard question to answer, but the smiles in Vila Canoas, seen from up-close, are the same smiles of Sao Conrado or Leblon. No matter the lens or perspective you use to look at Rio de Janeiro, despite of all, the city is full of gestures of kindness. Of proud and gentle people.

I know of no other place in this planet where the nights can so easily become a celebration of rhythm and people are so ready to smile.

Tweet

No hay comentarios.:

Publicar un comentario

Se reciben comentarios: